The Next New Things – Next/El Bulli – Chicago

There can be no doubt that the El Bulli meal, currently being prepared to the lucky few at Grant Achatz’s (and David Beran’s) stylish restaurant Next is an event. Perhaps too much of one, as museum retrospectives often are.

A word of background. A year ago – February 2011 – I was fortunate to dine at El Bulli itself, outside the Catalan tourist town of Roses, situated by a curving shoreline road in what seemed in the Spanish dark the middle of nowhere. Next is, in contrast, in the middle of everywhere: ground zero of culinary Chicago.

After 42 courses and six hours I left astonished, astounded, and amazed. Chef Ferran Adria, a gracious and warm host, had created a menu of themes – prawn courses, Mexican plates, black truffles galore, a tribute to woodcock. The meal was a magnificent collection of gastro-symphonic riffs. In the final months of El Bulli, Chef Adria had managed to combine modernist techniques, incredibly sourced ingredients, and a style that reflected a recognition of the continuing importance of classical cuisine. The meal was an essay on the passions and theories of a chef in action. The courses represented a conversation with the diner as well as with the land. When I die the memory of that meal will be on my lips: my last exhalation.

And so we find Chicago’s Next – and Chicago’s Alinea. Dining at Alinea, one has a sense that is perhaps as close to dining at El Bulli as anywhere else on these shores. Through his cuisine Chef Achatz works through a set of themes. As in Catalonia, the meal in Lincoln Park is a conversation: techniques, ingredients, and theories of food. Dishes whisper amongst themselves in profound, harmonious, and sometimes jarring fashion.

Next is different: a museum, not an atelier. At $485 (tax and tip, added), 29 courses, and five-and-half hours (330 minutes), the meal is a rousing success. I do not regret being one of those internet groupies who purchased season tickets (I was assigned number 1049, only a very few after me were privileged to allow Nick Kokonas to hold their cash interest-free for the year).

Unlike meals at Alinea or at El Bulli itself, Next is a commemorative celebration. The twenty-nine dishes cribbed from the El Bulli playbook are selected from recipes stretching from 1987 to 2010. One score and four years. As each course was presented, the server meticulously noted its year of birth. Had the meal been organized differently this could have permitted diners to gain a sense of the development of Chef Adria’s cuisine, and it did develop creatively over a quarter-century. The early dishes were recognizably 1980s haute cuisine. It is easy to imagine the 1988 Suquet of Prawns (shrimp stew) being served – and being loved – at the opening of Charlie Trotter’s. Later shapes and colors explode, food architecture enters, and then modernist (molecular) techniques are common. One expects a genius to develop in a quarter-century of practice, and Ferran Adria is a genius.

The problem is one of balancing the type of dish against its historical moment. The dishes were presented in a higgly-piggly chronology: 2003, 1997, 1992, 2001, 2000, 1988. Logic was evident in ingredients and in size (snacks before appetizers, fish before meat, palate cleansers before dessert), but the discussion among the dishes was muted. In an early menu at Alinea, Chef Achatz brilliantly doubled the progression: savory to sweet, and then a reprise, savory to sweet again. It was as stunning intellectually as it was in gustatory terms. But here at Next one lacked this sense because the dishes were ripped from time. And the diner was left with a parade of courses: magnificent, fine, odd, and off. The grand thematic linkages – the compelling connections among the platters – that were so compelling at El Bulli were less evident on Fulton Market.

Although the food is, deservedly, front and center, it is the service that shaped the evening both as exhilaration and as frustration. The frustration first. We were informed that the meal was planned to last 3-1/2 hours. But by 11:30 (with an 8:00 reservation) we were nowhere close. Enough already. It wasn’t that we were slow eaters, but the gaps between courses were notable. Admittedly this was only the second week of public service and Next is known as a work in progress, but by the time that we staggered onto Fulton Market at 1:30, we truly staggered. This was compounded by the servers’ generosity with wine. A lot of vino spilled upon our shores as our cups ran over (the wines were well-chosen, mostly from southwest France or Catalonia). Three-and-a-half hours seem an unlikely goal, but four hours is a target. If El Bulli can pull off 42 courses in six hours, 29 in four should not be impossible.

Now the exhilaration. Perhaps it was still early in a long run that may become routine, but the servers were positively joyous, and helped to create a communal, convivial atmosphere (even sharing that Chef Achatz was sitting nearby: he arrived later, left earlier, but perhaps he chose the children’s menu). We were served by a team that seemed highly professional, but also congenial in a Midwestern way. With the exception of one dish that was not explained properly (more on this later), we felt warmly enveloped throughout the night.

As is true in Roses, one begins with a set of snacks, presented in rapid order, and which, taken together, revealed some of the techniques for which El Bulli has become esteemed. First was Nitro Caipirinha with Tarragon Concentrate (2004, Ferran in his chemistry days), a frozen (with liquid nitrogen) play on the Brazilian cocktail of cachaca, sugar, and lime with the addition of a small, but potent bit of emerald green tarragon concentrate. The drink, otherwise perhaps not so different than a frozen daiquiri, is transformed by the power of deep herb. It is an impressive reminder of how a powerful morsel matters.

Immediately after, we were treated to Hot/Cold Trout Roe Tempura (2000) a dish elevated by the light tempura batter blanketing the salty, cool trout roe. The combination was worthy of a fine restaurant, even if the snack seemed more a blind date than an integration of tastes.

Third was a nifty little coca of avocado pear, white sardine, and green onion (1991). This was early Ferran, where the wise combination of ingredients was central to gustatory pleasure. At most restaurants this would be a very successful amuse, tonight it was a very pleasurable throwback.

The fourth dish, iberico sandwich (2003), was a bit of a disappointment. A fine slice of iberico ham was draped over a cracker. The ham was a taste of Catalonia, but the dish was a moment to catch one’s breadth in the hopes of greater excitement ahead.

The next snack provided that excitement: El Bulli’s canonical spherical olive (2005). The label is perhaps startling: aren’t all olives spherical. Yes, but not all spheres are fully liquid, contained within a thin bladder of alginate, another innovation from Ferran’s molecular moment. The juicy olives are liquefied and placed in an alginate bath, and – boom! – reverse spherification. Here is the discovery of a quark, and culinary inspiration marches on. Granted that this is (necessarily) a liquid one-bite wonder, and it tastes, after all, like very potent olive liquor, but it is the zenith of molecularity.

The Golden Egg (2001) is a quail egg yolk in a caramelized shell. Here the texture was the star of the dish which otherwise was slightly sweet and slightly unctuous.

Lucky Seven. The star snack was surely Liquid Chicken Croquettes (1998) from a moment at which Chef Adria was playing with the possibility of textures. These tiny croquettes were filled with potent liquid chicken: not chicken soup, but intense chicken syrup. To this point, this small dish was the heroic moment of the evening.

Liquid chicken was paired with Black Sesame Spongecake and Miso (2007). Black sesame has a powerful, nutty flavor, and this flavor was nicely matched with the airy texture of the floataway cake. Only a bite or two, but a very beautiful, rich combination.

We moved into more substantial dishes, including Smoke Foam (1997), a dish that our server described as a provocation, incorporating leaves, twigs, and bark: gelatin and water, flavored with wood smoke. Chef Achatz has also embraced smoke as provocation (as in several dishes at Alinea and in the Childhood menu at Next). The goal is not to create a dish that is easy to like, but that is important to think. Perhaps it is a paean to toast or to marshmallows, but the glass was more successful as idea than as a beaker for a pleasure potion.

Ten was textured stunner. Carrot Air with Coconut Milk Curry. With today’s foamy overuse, this concoction reveals the power of the foam form. The flavor of carrot and coconut was intense, the orange color was luminous, and the pleasure of slurping air was palpable. This was one of the most exciting and memorable presentations of the evening, revealing that even what has subsequently become a somewhat dull technique can be brilliant in the mind of a master.

The 1997 Cuttlefish and Coconut Ravioli with Soy, Ginger and Mint was one of those moments in which dishes spoke to each other. The coconut reprised the soupy air of the previous dish and also had an Asian inflection. The texture was powerfully distinct, chewy and smooth, rather than evanescent. The pairing of the dishes echoed in the gullet.

Dish 12 could have been 13 for all the luck it brought. Tonight the colder the dish, the less successful. I reject Savory Tomato Ice with Oregano and Almond Milk Pudding (1992). Too salty, too icy, and too bland (the milk pudding). A trifecta failure with a set of textures than lay uneasily in the same martini glass. Perhaps 1992 was an off-year in Roses.

The real dish 13 was far more successful. Hot Crab Aspic with Mini Corn Cous-Cous. The corn cous-cous was rather plain, but the crab aspic was heroic, the gelatin had just the right textural give as visually the crab provided a dark intrigue.

The next dish, reconceptualizing the idea of cous-cous to better effect, creating vegetable pearls surrounded by a garden ring, was the most inspirational dish of the night: Cauliflower Cous-Cous with a Solid Aromatic Herb Sauce (2000). Perhaps this was the moment that Ferran Adria became a genius. Not having it in Barcelona, I can’t assess whether Next’s version was identical, but the Next kitchen deserves warm regard in creating or recreating a dish that was simultaneously savory and sweet with enough lamb jus to give it a meaty aspect. Its complexity was astonishing: creating a dish that must have drawn from every domain of aroma and texture, creating a plate in which to eat was to engage with a wealth of choice. Adria reconsidered the relationship between liquid and solid, sweet and savory, and meat, vegetable, and grain. This wreath is a moment of breath-taking circularity in culinary history.

The fifteenth dish was our halfway point: Suquet of prawns (Spanish shrimp stew) (1988) was an early and elegant dish, one that might have been served at Trotters or other grand restaurants from a quarter-century ago. It was beautifully designed and conceptualized with a powerful oceanic taste matched with dancing herbal and vegetable textures.

Potato Tortilla by Marc Singla (1998) reflected Adria’s borrowing of the idea of hot foam in what was essentially a potato soup. I found this more of a pause in the progression than an occasion for merriment.

Trumpet Carpaccio (1989) is another early dish, a tribute to fungus. Its elegance is stirring and, so long as one enjoys mushrooms (as I do), this carpaccio is a memorable construction. This was an earthy preparation of the very best sort.

Unfortunately I seemed not to have taken a picture of the prettiest of all of the dishes. It was late, I was tired. Red Mullet Gaudi (1987) was the earliest dish recreated and was a tribute to Ferran’s fellow Barcelonan, the visionary architect Antoni Gaudi, creating a dish that was reminiscent of his lizard-like mosaics in the breathtaking Parc Guell in Barcelona. Here mullet was covered by tiny mosaics of tomato, shallots, red peppers, and other delightful vegetal nubbins. The taste was impressive, and the decoration was remarkable. The fish was placed on a warm bag of watery shells adding to its visual and tactile complexity.

The next plate (again no photo) combined land and sea, flower and meat: Nasturtium with Eel, Bone Marrow, and Cucumber (2007): a triptych. Certainly a sturdy dish, but not a show stopper.

Dish 20 was the big protein: Civet of Rabbit with Hot Apple Jelly (2000). The grand combination of fruit and game proved successful, and the style of presentation reminded us that before the molecular style hit these shores there was Ferran working his magic. The dish typified what we have come to know as modernist presentation, full of lines and dashes, smears and dust.

We moved toward dessert, but with a hiccup. Chef Adria is known for his “balloons” – icy, hollow spheres capturing some savory or sweet flavor. Tonight’s sphere was a “gorgonzola balloon” (2009): a little blue cheese goes a very long way. After a nibble or two, it was time to move on. Another balloon might have hit the spot, not tonight.

The next step toward dessert was the foie gras caramel custard (1999), which fortunately Next can now serve in Chicago: no airfare necessary. The dish was pleasant, but tasted as its name revealed.

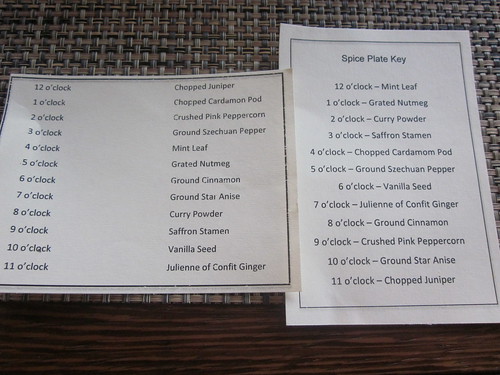

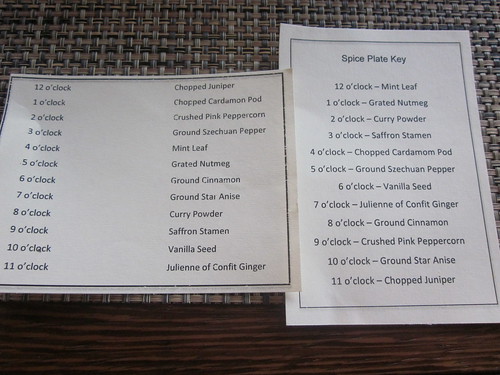

Dish 23 revealed the chef at play: Spice Plate (1996). We were served a ramekin with a thin green apple gel and with a dozen bits at the points of the clock around the edge. And we were presented a card that listed the hour and the ingredient. Unfortunately – and here is the staff gaffe – we weren’t told that we were supposed to figure out which ingredient belonged where, and we were puzzled that the listings were wrong or that we were so exhausted that we couldn’t tell mint from curry. Eventually we were presented with a key, and all was well, even if the dish itself was more of a jest than a classic.

Mint Pond (2009)(not pictured) was peppermint powder, green matcha tea, cocao powder, muscovado sugar over ice. No photo. This was another failure. A bowl of ice was presented with a thin layer of ice on top on which powders of mint, tea, cacao, and sugar sprinkled. It was supposed to be a palate cleanser, but on this Chicago winter night, it seemed like just more ice.

Much more impressive was the Chocolate in Textures (1997), a complex architecture of cacao. The presentation was deep and dark, and surely the finest dessert of the night. Here was architectural food, never forgetting that dessert must build on the foundation of the sweet and smooth.

Three quick desserts were served together – and as one a.m. had passed, we were grateful indeed: liquid filled chocolate donuts (2010, a dish that I was served in Roses), a crème flute (1993), and a beautiful and complex puff pastry web (1989), revealing a true sensitivity to pastry as a form of construction. They were a nice way to edge toward closure.

Finally – 29 – the mignardises – luscious passion fruit marshmallows with latex hands to wish us b’bye.

It has taken me almost as long to compose this essay as it took Next to serve the meal on which it is based. True enough. But I could have been more efficient as well. The clock is a tough master.

But ultimately time spent slides into forgetting, and the food remains. And how was it? Worthwhile without doubt. For me Next’s El Bulli dinner did not match El Bulli’s El Bulli dinner. The focus was more respectful retrospective than startling immediacy, but there were astonishingly great dishes and many excellent ones as well. Excluding the icy claptraps, I was grateful and delighted and impressed with Chef Beran’s mastery and Chef Achatz’s inspiration and Chef Adria’s genius. There is, however, a danger with a survey; often it is the surrounding dishes that spotlight the acts of brilliance.

For those who have not had the fortune to reach El Bulli, Next is a very excellent Next-best-thing. For those who have, Next’s showy creation captures much of what was remarkable about that now-shuttered bulldog of a place. At Next flaws, yes, but also an abundance of astonishing vistas of texture, vision, and, always, taste.

Next Restaurant

953 W Fulton Market

Chicago, IL 60607

http://www.nextrestaurant.com

Noma Interior

Noma Interior

Noma Interior

Noma Interior

Flatbred with Malt Flour and Juniper (in vase)

Flatbred with Malt Flour and Juniper (in vase)

Sauteed Raindeer Moss with Mushroom Powder

Sauteed Raindeer Moss with Mushroom Powder

Blue Mussel and Celery (one edible mussel)

Blue Mussel and Celery (one edible mussel)

Crispy Pork Skin and Black Currant (I think)

Crispy Pork Skin and Black Currant (I think)

Apple, Smoked and Dried Cucumber

Apple, Smoked and Dried Cucumber

Cheese Biscuit, Rocket and Herb Stems

Cheese Biscuit, Rocket and Herb Stems

Potato Sandwich with Duck Liver Mousse and Black Trumpet Mushrooms

Potato Sandwich with Duck Liver Mousse and Black Trumpet Mushrooms

Grilled Dried Carrot on Ash and Sorrel Emulsion

Grilled Dried Carrot on Ash and Sorrel Emulsion

Caramelized Milk and Shaved Cod Liver

Caramelized Milk and Shaved Cod Liver

Pickled and Smoked Quail Egg

Pickled and Smoked Quail Egg

Radish, Soil, and Grass

Radish, Soil, and Grass

Aebleskiver and Muikku (Finnish Fermented Fish)

Aebleskiver and Muikku (Finnish Fermented Fish)

Sorrel Leaf and Cricket Paste (inside the leaf) with Nasturium

Sorrel Leaf and Cricket Paste (inside the leaf) with Nasturium

Glazed Snails with Parsley and Watercress

Glazed Snails with Parsley and Watercress

Danish Potato with Butter Sauce with Peashoots and Sorrel Leaves

Danish Potato with Butter Sauce with Peashoots and Sorrel Leaves

Sous Vide Fava Beans and Beach Herbs

Sous Vide Fava Beans and Beach Herbs

Wild Berries and Cucumber Salad

Wild Berries and Cucumber Salad

Stone Crab with Parsley Puree, Verbena and Seaweed Broth and Egg Yolk

Stone Crab with Parsley Puree, Verbena and Seaweed Broth and Egg Yolk

Pike Perch with Butter Foam and Cabbage, Verbena and Dill

Pike Perch with Butter Foam and Cabbage, Verbena and Dill

The Hen and the Egg, cooked with Hay Oil, Spinach, Nasturium, Oxalis, and Parsley Sauce

The Hen and the Egg, cooked with Hay Oil, Spinach, Nasturium, Oxalis, and Parsley Sauce

Sweetbreads and Bitter Greens, Celeriac and Chantrelles, Juniper Root

Sweetbreads and Bitter Greens, Celeriac and Chantrelles, Juniper Root

Open Ice Cream Sandwich with Ant Puree

Open Ice Cream Sandwich with Ant Puree

Ice Cream Sandwich with Blueberry Sorbet and Ant Puree with Nasturium Leaves

Ice Cream Sandwich with Blueberry Sorbet and Ant Puree with Nasturium Leaves

Gammel Dansk (Bitter Danish Liquor) with Sorrel and Dried Milk

Gammel Dansk (Bitter Danish Liquor) with Sorrel and Dried Milk

Noma

Strandgade 93

1401 Kobenhavn K, Denmark

3296-3297

http://noma.dk

Noma

Strandgade 93

1401 Kobenhavn K, Denmark

3296-3297

http://noma.dk